Bi(wo)manual exam

An exam that only involves vaginas, cervixes, uteruses, and ovaries, yet the word "man" is at the center? Atrocious. That's biwomanual exam to you! (Welcome to my mind, exhausted with such things.) Also, only in taking the above picture did I realize how Michelangelo "The Creation of Man"-esque the exam is. Goodness the parallels there are never-ending: the uterus as womb for creating people, uterus as a central argument of male-dominated politics, the uterus itself connected to both the outside and the inside worlds by the cervix... and my partner liked the idea enough that we bring you this:

I digress. Back to the post.A well-woman (or, for those whose gender expression does not identify with woman, well-vagina-cervix-uterus-ovaries) visit typically encompasses a health history, physical exam including breast and pelvic assessments, labs such as a pap smear and sexually transmitted infection (STI) screen, general health maintenance such as checks for cholesterol, diabetes, weight and exercise, and social history to ensure safety and well-being, not to mention actually getting to know the woman-as-person. (My thought in typing this up is, how do I ever complete this in 15 minutes?!? I never do… and there is some awesome conversation happening lately on the fqhcmidwives ACNM listserv about time restraints in FQHCs. If you're interested, join!)My focus lately is the pelvic exam, and within that category, the bimanual exam. The pelvic exam usually includes an external assessment to sure everything in the area of the mons, vulva and the rectum appears normal; a speculum exam to visualize the cervix and the vaginal walls; a pap smear and other vaginitis screens; and a bimanual exam. The bimanual exam involves a provider inserting one or two fingers of one hand into the vagina to assess vaginal tone and cervical motion tenderness (CMT), while the other hand palpates the uterus and ovaries through the abdomen. Both hands together assess for uterine position, tone and size of the uterus to assess for fibroids and tenderness, and adnexal tenderness around the ovaries. Two hands = bimanual. Here is a more official picture. For non-providers reading this post, I am sure that as you read this description, you are reminded of your own health history with bimanual exams, and perhaps remember a particularly gentle one or particularly rough one. For providers, there are likely a few tangible exams in your memory, good or bad, and the others generally run together. For both provider and patient, these exams are a connection, a moment, one of the most intimate places shared between two people, and shared in a healthcare setting.As both a provider and a woman who receives healthcare, I have questions. Why the bimanual exam? What is its purpose and its effectiveness? What do people think of the intimate nature of the exam as a whole? As of late, I greatly question the role of the bimanual exam in the regular health screening of women. I need to know more, and I think you all might also appreciate this information, as women, receivers of healthcare, and givers of healthcare.Let’s take a step back. First and foremost, providers must learn how to assess the internal organs of the cervix, uterus, and ovaries. So, how do we learn the art of the bimanual examination? Since I have already described the nuts and bolts / vaginas and ovaries involved, I will reference these resources more for their particulars related to the exam itself.

For non-providers reading this post, I am sure that as you read this description, you are reminded of your own health history with bimanual exams, and perhaps remember a particularly gentle one or particularly rough one. For providers, there are likely a few tangible exams in your memory, good or bad, and the others generally run together. For both provider and patient, these exams are a connection, a moment, one of the most intimate places shared between two people, and shared in a healthcare setting.As both a provider and a woman who receives healthcare, I have questions. Why the bimanual exam? What is its purpose and its effectiveness? What do people think of the intimate nature of the exam as a whole? As of late, I greatly question the role of the bimanual exam in the regular health screening of women. I need to know more, and I think you all might also appreciate this information, as women, receivers of healthcare, and givers of healthcare.Let’s take a step back. First and foremost, providers must learn how to assess the internal organs of the cervix, uterus, and ovaries. So, how do we learn the art of the bimanual examination? Since I have already described the nuts and bolts / vaginas and ovaries involved, I will reference these resources more for their particulars related to the exam itself.

- Textbook explanation

- YouTube and internet resources

- Synthetic pelvic models and simulators

- Gynecologic teaching associates (GTAs)

- Student cohort exams

- Women undergoing anesthesia and consenting to medical student teaching

Let’s break these down:Textbook explanationVarney’s Midwifery:"Remember to use a firm but gentle touch and to be alert throughout the examination to any indication from the woman of discomfort or tenseness that might cause her to tighten up or move away from you." (p. 1182)In standard step-wise approach in the skills section of Varney's, there is an explanation of procedure, findings, and significance. However, the skills section also seeks to provide a rationale for each skills examination, and here the skills rationale is lacking. In the significance section, there is important information on finding cervical motion tenderness (CMT), a non-midline uterus that could indicate masses or adhesion that would displace a normally centered womb, and checking for organ prolapse into the vaginal sheath. This is all important information for following-up on reported symptoms such as pelvic pain, dyspareunia (pain during sex), or concern for a long-standing gonorrhea/chlamydia infection, one might think, but not for general screening. That is my thought, anyway.Kerri Durnell Schuiling and Frances E. Likis' Women's Gynecologic Health:"Few experiences that women encounter in the evaluation of their health are as intimate and thus potentially anxiety producing as this examination. All providers who perform the pelvic examination have the professional responsibility to carry it out proficiently, promptly, and respectfully. Each woman brings her own past experiences and her own needs to the present examination." (p. 114) "Inform the woman that the next step is examining her reproductive organs internally with your fingers." (p. 120)A concise introduction into the exam, and love the holistic and historical thought process they bring up here. Though these authors also provide a step-wise approach to the exam, there is little discussion of rationale.YouTube and Internet resourcesBest video I found on YouTubeVery clear in its step-wise approach. Not much rationale.Best internet resource

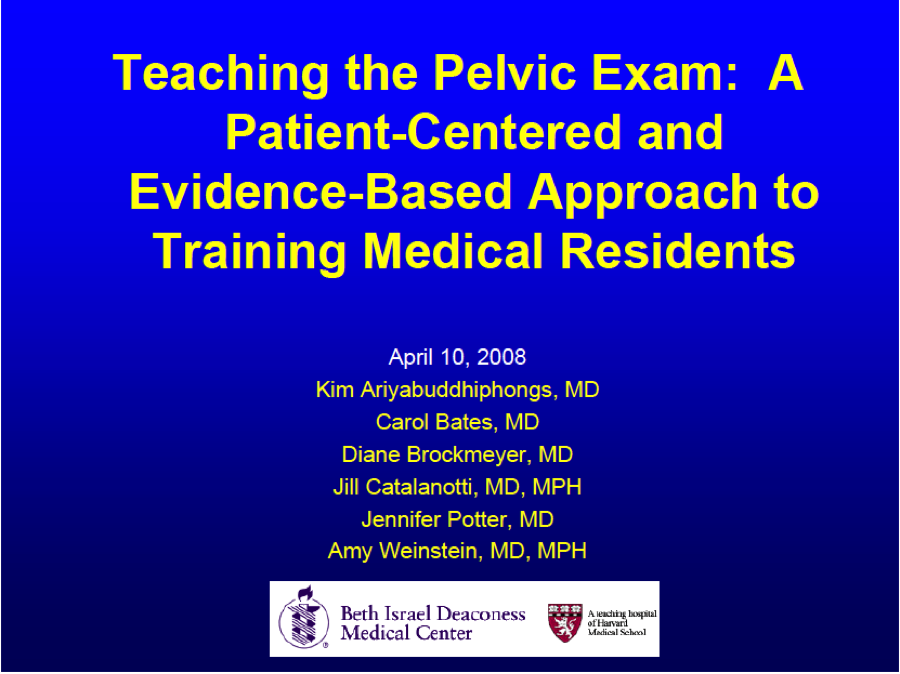

I really like the specifics this Powerpoint gives, including sensitivity and specificity of the exam itself. Additionally, this presentation discusses women with history of sexual trauma, visual and hearing impaired, exam tables for all body types, positioning without stirrups, speculum choice, and overall approach. AWESOME PRESENTATION. Please note: the screening guidelines are completely out-of-date, so ignore those.

Synthetic pelvic models and simulatorsAlso discussed in the Powerpoint presentation above, synthetic models have their purpose in initial teaching. With little feedback as to the provider's approach, including gentle-ness, placement of the thumb with the internal hand, and delicate differences between vaginal tissue and cervical muscle, these have their limits. Such pelvic models, that display the vagina and little else of the woman's person, are substantially concerning in their indirect teaching of vagina-as-not-connected-to-person teaching in non-holistic teaching modalities. If anything, a vagina model without a woman's face encourages the learning provider to dissociate the exam with the woman as a whole, and is thus promoting of a similar medical approach to the exam as one would employ to the foot or arm.Just looking at pictures of the synthetic models made me uncomfortable when they were not attached to a full body, and made me think very quickly of vaginal simulators used as sex toys. In the world of sex toys, I am supportive of whatever makes people feel good and is safe for all involved, but in the world of healthcare learning, I am concerned about that association.Gynecologic teaching associates (GTAs)In my midwifery program, there were individuals who participated in a paid program to teach student providers of all types to learn how to do breast and pelvic exams. These women were incredibly familiar with their own bodies, knew what a proper exam should feel like and the appropriate language a provider should use, and could direct individuals students left, right, and less/more pressure as needed. Their paid position and knowledgeable role provided a modicum for their consent and an outlet for liability concerns, which is incredibly important. I have so, so much respect for these women, who actively participated and supported this work to teach students how to properly perform these sensitive and sometimes difficult-to-learn exams. Particularly with the bimanual exam, at times the uterus and ovaries are difficult to palpate, and having at least have felt them once by someone who can verify what you are feeling, since it is in her own body, is immensely helpful. There is also some research, and some history in starting these programs, showing the effectiveness of this teaching model. (Importantly, there are also men who participate in a similar program to teach rectum and prostate examination.)Student cohort examsWhat does this mean? This means that a bunch of student providers who are learning the exams, who have already learned by other means and would like more practice before examining a patient, may get together as a group and volunteer themselves for each other. Does this happen, you ask? It absolutely happened in my student cohort, and I am so thankful to have had that opportunity to learn more about the diversity of exam findings and language suggestions by my fellow (awesome) student providers. Does it happen outside of my cohort? It came up at a midwifery dinner the other night that at almost every midwife's program this was an option, whether school-sanctioned or otherwise.Midwifery students from Columbia University wrote a letter to the Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health describing their appreciation of this opportunity, and its importance in midwifery education."Midwives do not provide medical care, but midwifery care. This is a distinction we should relish, not erase... Peer pelvic examinations have a unique ability to serve as a reminder that the foundation of a good examination comes from compassion and mindfulness. A good examination is not just about assessment and diagnosis; it is about seeing woman as woman and not object, it is about empowerment."Beautiful points in learning to care, to really care, for women, by caring for those you know first. Wonderful.However, this is a controversial topic in midwifery. What are the concerns about students learning on each other? Amy Levi, CNM, PhD articulately outlines them in the article “Examining Ourselves: Exploring Assumptions about Teaching Pelvic Examinations in Midwifery Education.” She reviews the history of the feminist movement reclaiming women’s health exams, medical student exams under anesthesia, and possible concerns about midwifery cohort self-examinations. Main points regarding concerns for this scenario include:

- Expectations that students will participate; removes voluntary consent

- Concern for discovering abnormal findings during the exam, and the student-provider knowing personal health information about the volunteer

- Issues of potential assault or battery during the exam, at the educational institution

Pelvic exams on women under anesthesiaThis is a practice by which women consenting for medical student involvement in teaching hospitals may also indirectly consent to medical students learning bimanual exams while women are under anesthesia. In this way, students can ensure they are correctly feeling the organs as teachers ensure appropriate palpation, as the women's discomfort is not an issue, and then perhaps more gentle palpations happen in the future. Do the women know they have consented to this exact teaching? Nope. This is a big topic, brought to light again recently due to some media attention here and here. The history is totally covered here and here thanks to Jill Arnold at Unnecesarean.com. Typically, women who are prepped for surgery have their face and bodies covered, so the student is only associating that exam with the vaginal organ, rather than the whole person, especially since she is not able to speak, express pain, or move away. I repeat my issue with the simulators above, since this is what the women are being used for in this instance: teaching without any direct health benefit.Everyone take a deep breath, let's talk about that another time, and get back to the issue of the usefulness of the exam itself.Now that we have covered all of that, let's talk about why we perform the bimanual exam at all? What are we looking for with that exam, in terms of screening?

- Vaginal tone, aka strength of the vaginal muscles, and concerns for bladder or rectum prolapse into the vagina, particularly for symptomatic women who report dyspareunia, abnormal vaginal bleeding, or urinary incontinence.

- Cervix, its smoothness, any cysts or masses, and tenderness indicative of infection if other signs of infection have been discussed. Cervical cysts and masses could also be indicated in reports of dyspareunia.

- Uterus, its size, mobility, tenderness, position in the pelvis, and presence of masses. Uterine position is especially important for IUD insertion, abortion provision, and endometrial biopsy use, as information about the direction the uterus is pointed in helps the provider to know how far into the uterine cavity to go with instruments.

- Ovaries, including their size, presence, tenderness.

- And, possibly, pelvic measurements through pelvimetry.

And what about for women with symptoms? If a woman has complaints of pelvic pain, dyspareunia, abnormal vaginal bleeding or other abnormal vaginal complaints, a bimanual exam could provide further information for the provider's management plan. Makes complete sense, right? Wrong. Time and again, the bimanual exam does little to help us in the next steps of the management process.The first two studies consider the "ideal circumstances" to be women under anesthesia, who might be palpated to provider need in determining the organs, which could also be assumed to be with great depth and force of palpation. However, couldn't one also consider the fully sensitive women more ideal, when screening for asymptomatic disease also hinges on tenderness, which the woman describes? Food for thought. Additionally, these are four studies of many that indicate little relevance and importance of the bimanual exam as a whole. Not one indicated that the bimanual exam was an awesome screening tool. If you find one that says that, please send it my way.

- Limitations of the pelvic examination for evaluation of the female pelvic organs. Padilla, et al., International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2005. Conclusion of the study of 84 women assessed under anesthesia with assessment outcomes compared to surgical observations? "The bimanual examination appears to be a limited screening test for the female upper genital tract even under the best possible circumstances. Uterine assessment appears to be more accurate than adnexal assessment."

- Accuracy of the Pelvic Examination in Detecting Adnexal Mass. Padilla et al., Green Journal, 2000. Similar model to the study above, 140 women under anesthesia for pelvic surgery consenting to bimanual exam, comparing findings of the manual finding to the surgical findings: "Bimanual pelvic examination has marked limitations for evaluating adnexa, even with idea circumstances."

- Is there any value in bimanual pelvic examination as a screening test? Grover and Quinn, The Medical Journal of Australia, 1995. Asymptomatic volunteers, an awesome 2623 of them, participated in bimanual assessment and then ultrasonography for validation. Conclusions: "This 'routine' procedure is undertaken in the belief that it serves a screening purpose. The detection of benign uterine abnormality is of no clear benefit as progression to malignancy is rare. Bimanual pelvic examination is of questionable value as a screening strategy in view of the low incidence of ovarian cancer in healthy women, and the relatively high prevalence (1.5%) of relatively unimportant adnexal abnormalities." Well-said.

- Do new guidelines and technology make the routine pelvic examination obsolete? Westhoff et al., J Women's Health, 2011. A commentary on updated pap smear guidelines with less frequent recommendations and its effect on bimanual exams. "No evidence identifies benefits of a pelvic examination in the early diagnosis of other conditions in the asymptomatic woman. Speculum and bimanual examinations are uncomfortable, disliked by many women, and use scarce time during a well woman visit."

What is the concern with the bimanual exam? Or, what should I say, are my concerns? Great that you ask! I have a few.

- Research as to the effectiveness of the exam in finding abnormalities in asymptomatic women. As noted above, this is fairly debunked.

- On top of that… connection to the updated pap smear guidelines. For women with a history of normal pap smears, we are now testing every three years (for ages 21 to 30) and every five years (for ages 30-65). This is indicative of largely normal findings, the body clearing up infection before we go and over-test, and pointing to the possible un-need of internal exams on the regular.

- And even more on top of that... the intimacy of the exam for all involved. For the women receiving the healthcare and the provider providing it, this is an intimate experience. A sex organ is involved, despite what medicine wants everyone to believe. (Here, I would like to give a nod to everyone involved in the orgasmic birth movement, for those women lucky enough to find birth stimulating rather than painful, involving that same sexual organ.)

I have also had a few friends and patients say things that make me feel uncomfortable about the exam as a whole, performed carte blanche on each woman as a screening tool. One very close friend, very in-tune with her body, asked me, “Why do you all do that?” And I answered, similar to the long-winded typing I have above. Then she responded, “Well I figured it wasn’t a free finger.” A laugh and cringe moment, but a point well-made.A patient recently prefaced her exam by describing her discomfort with the exams in the past. I spoke my careful speech of how it should never hurt, should feel like pressure, and if at any point she wants me to stop just tell me and I will. I ensured that she felt in control, that we could stop at any time, and that we could always complete any part of the exam a different day. We spoke and had normal conversation throughout the exam. After the exam, concluding with the bimanual portion, she said to me, while laughing and touching my arm, “I feel violated.” I felt awful, but also sensed that she was trying to make light of a moment in which she felt very uncomfortable. But that word, violated, means something.There is also this cultural reference from the television show, Scrubs, which really makes me cringe in absolute discomfort as a women’s health provider, and then laugh about its total ridiculousness in people's misunderstanding about what we are doing "down there." Totally awful, but really begs the question of the sexy-vagina and healthy-vagina connection.Male providers are legally required to have a female chaperone in the room with them when performing a pelvic exam due to the intimate nature of the exam and concern for assault or battery. Up-to-Date recommends this consideration for any and all providers. As I have mentioned in other posts, I have had a few patients for whom consent was difficult or I felt I could have been approached by the patient afterward for inappropriate practice due to the patient’s mental health issues even with prior consent, and so at times I have requested to have a nurse or medical assistant in with me during an exam. There is such a heterosexual and male-dominated assumption of sexual assault that is pervasive throughout healthcare, to the point where this is legally mandated. I think this is totally appropriate in many ways, but encourage providers and women alike to consider the need for a chaperone in any intimate exam of this nature.And what of consent? Many sources cite cooperation with the annual exam as consent, reviewing the full procedure prior to beginning and not hearing “no” at some point in the exam, etc. But do women know they can decline this portion of the exam? Is it a portion of the exam that many would decline if they knew its efficacy? Is it a surprise for many that it happens at all, comes immediately after the speculum exam and immediately before the glove-removal-handshake-and-good-bye-I’ll-call-you-with-the-abnormal-results? No woman has been concerned or expressed confusion when I have discussed what comes after the speculum exam, and so once they are positioned, the exam continues how I see fit.In considering the incredibly unethical nature of students performing bimanual exams solely for the purpose of learning on women under anesthesia, this connectedness between the sexual and the health becomes even more tangible. Women are violated vaginally when they are not awake and are digitally penetrated vaginally or rectally (or for that matter, buccally), have not consented or been given the opportunity to decline such penetration, or are not informed of that penetration upon waking up from the anesthesia. What of a subsequent infection of yeast or bacterial vaginosis due to the lubrication or assessment itself? The woman could be incredibly concerned where that vaginitis may have originated. What of women who have never had sex, and have an intact hymen? What if the student assesses an abnormality and does not follow-up or know enough to report to the instructing provider? Completely inappropriate, of course, but these points are important in that argument.Connecting the ‘vagina as sexual organ’ with the ‘vagina as receiver of healthcare’ is critically important to issues of consent, liability, patient-provider relationship and a patient’s long-term experiences with her vaginal healthcare. For women who have been violated, abused, assaulted, have not yet started to have intercourse or may have been abstinent for a long period of time, the bimanual exam can be an incredibly intimate or uncomfortable exam, a positive or negative experience, in reflection may feel differently than in the moment, as may always be the case when an activity is connected with a sexual organ. Violation of that organ is in the eye of the beholder, experienced by that person despite the work of the provider, and patient support whether in the form of a chaperone or friend, should be considered for all patients.In considering the bimanual exam as a screening tool, it is important to comment that almost the entire annual exam is a screening tool. The clinical breast exam, the external vaginal exam, and internal exam largely include components related to screening and not diagnosis. If anything is found during those exams, follow-up or further diagnostics are indicated. However, in asymptomatic women, or in women who do not request the exam due to a concern, there seems to be little need.Speaking with my partner about my concerns with the intimate nature of the exam, the point was made (again to drive home the main argument) that, what if, for penis assessment, there was a required 'few swipes of the penis' to assess for penile tone, similar to a hand job? This relates to the bimanual exam, as many people enjoy digital stimulation during sexual activity, as referenced by my friend's comment above. Similarly, a scrotum-squeeze, not unlike ovarian palpation in anatomy-speak, is not involved for asymptomatic men, but could be, and is an incredibly sensitive area to be involved in palpation for asymptomatic people. The turn-and-cough component is often a part of the physical exam for penis-owners, but perhaps there is similar concern for the sensitivity and specificity of that exam, and its intimate nature, as well. Finally, men may not request a provider based on sex, but could very well have a preference in this area, and are not given the same consideration related to their sex-organ and health-organ in the same way. Such genderized healthcare, pervasive across many components, needs greater consideration by all providers.In summation, I think the bimanual exam should be considered carefully in its usefulness in well-woman healthcare provision, consented for properly, analyzed in all settings for its potential liability concerns regardless of the genital anatomy or gender expression of the provider, and individualized both by provider and patient. I have decided to nix the bimanual exam in my annual patient visits, will no longer provide an automatic bimanual exam when following the updated pap smear guidelines, and will consider its approach in my assessment, management and plan of symptomatic women.I am pondering typing this up, in a different way, as a commentary article for the Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. I would love to hear your feedback to this preliminary pondering in women’s healthcare, to get an idea of what women and other women’s health providers are thinking about related to the bimanual exam.

- Do you always do a bimanual examination with the annual exam?

- What are your experiences with patient responses to the bimanual exam?

- In what way do your findings from the bimanual exam lead to changes in your management plan for symptomatic women?

- How are you changing your practice of pelvic exams as related to the update in pap smear guidelines?

- What are your thoughts related to chaperones present during pelvic examinations?